EvoInfra Strengthens Energy Transition Expertise

We are kicking off 2025 by announcing the expansion of our energy transition offering with Agnes Chan – this follows the arrival of Craig Jenkinson and Oliver Durston.

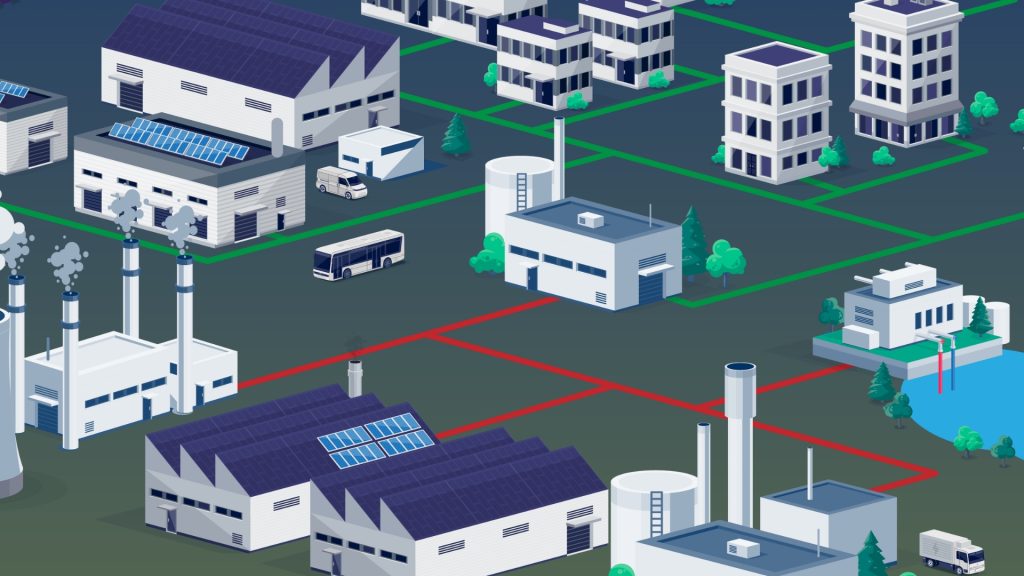

Ambition to Action: Heat Networks in 2025 and Beyond

2024 saw ambition finally being met with action, from significant investment into innovative and large-scale projects, policy development and enhanced consumer protections – laying strong foundations for further progress in 2025 and beyond.

What is a Debt Service Cover Ratio?

Understanding the Debt Service Cover Ratio (“DSCR”) is crucial in project finance, but it can be complex to navigate. In the first of our new series ‘Project Finance 101’, we break down the key aspects of DSCR.

Staffordshire Campus Living Wins ‘Deal of the Year’

We are proud to have acted as financial advisor to the Consortium and look forward to building on this success and supporting delivery of further transformative projects.

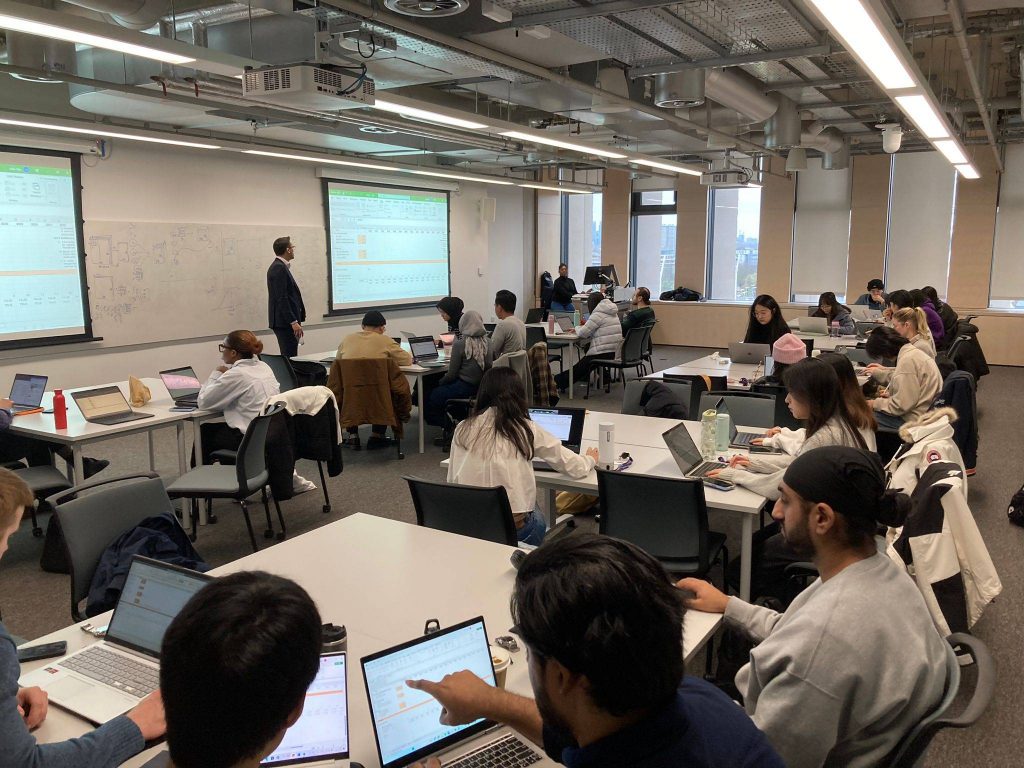

University College London (UCL) Financial Modelling Training

EvoInfra delivers financial modelling course to University College London (UCL), Bartlett School of Sustainable Construction.